An Exhibition by Angelo Pellegrini – La Chiesa del Santissmo Crocifisso, Barga Vecchia July 12-August 31, 2014

For more than half a century, Angelo Pellegrini has been wandering the Apuan ridges and Apennine meadows of the Garfagnana. Along the mountain roads and trails, he took thousands of striking, often poetic photographs, both in color and black-and-white. Early in his journey, he found a mentor and fellow spirit in Giovanni Pascoli — the cantore del mondo contadino, “minstrel of the peasant world,” one of Italy’s most celebrated writers from the 1870s to his death in 1912, and a resident of Barga’s Castelvecchio hills. Gabriele D’Annunzio, Pascoli’s contemporary and sometime rival, described him as “the last son of Virgil,” the epic poet and minstrel of Italy’s pastoral countryside 2,000 years ago.

Pellegrini’s admiration for Pascoli is the backdrop to an exhibition now at the Chiesa del Santissimo Crocifisso that will run through August 31. “It is about Giovanni Pascoli, not me,” he insists. But in myriad ways that Pascoli himself would have applauded, the exhibition is also about Angelo Pellegrini: his own enduring attachment to a contadino universe that is rapidly vanishing. “We are at the end of an epoch,” he says.

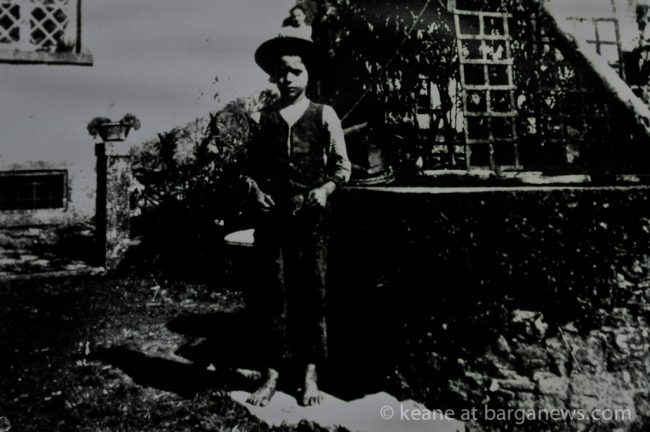

Under the title “Food in the Poetry and Prose of Giovanni Pascoli,” Pellegrini has assembled a survey of images and verses that do for that epoch what Virgil did for the Roman hinterland in the final century before Christ. The exhibition is an extended poem in its own right, combining selections from Pellegrini’s camera work with the words and personal photographs of Pascoli himself, and reproductions of paintings and engravings by the noted prewar Barga artists Adolfo Balduini, Alberto Magri and Umberto Vittorini.

As the title suggests, food is the exhibition’s organising principle, just as it is in the contadino world: the fulcrum of rural seasons, the essential link between the peasant and the land. Pellegrini has matched compelling images of this world with Pascoli’s observations — often in the dialect of his farmer-neighbors — on the symbolic and practical nature of olives and radicchio, milk, onions and eggs, all of which were products of his Castelvecchio garden.

But in the Garfagnana, as Angelo Pellegrini and Giovanni Pascoli both so memorably picture, the chestnut forest stands above all else in the hierarchy of food. It is home to the albero di pane, the “tree of bread,” the noble castagno. Its fruit has supplied countless generations with the milled flour used to make chestnut polenta, as well as bread, chestnut pasta and the delectable chestnut sweets known as neccio and castagnacci.

Sadly, it is precisely this central feature of the mondo del contadino that is waning, as documented by Pellegrini in photographs of venerable stone grain mills and farmsteads that have been abandoned to ruin. “Every detail that isn’t stone — the doors, the roof beams, the window frames, the furniture — was handmade from chestnut,” he says. “The castagno not only fed the contadini, it also provided their homes and their beds.”

These days, the local chestnut crop is a tiny fraction of what it once was. In part, this is due to the arrival of a parasitic Asian wasp, “dryocosmus kuriphilus,” which has decimated the chestnut crop in recent years. But the larger context is the disappearance of traditional agriculture from the mountains, along with the last generation of farmers whose methods date back to Virgil’s time. Their children and grandchildren have migrated to modern jobs (and modern food) in Italian towns and cities, and abroad to the United Kingdom, the Americas and Australia.

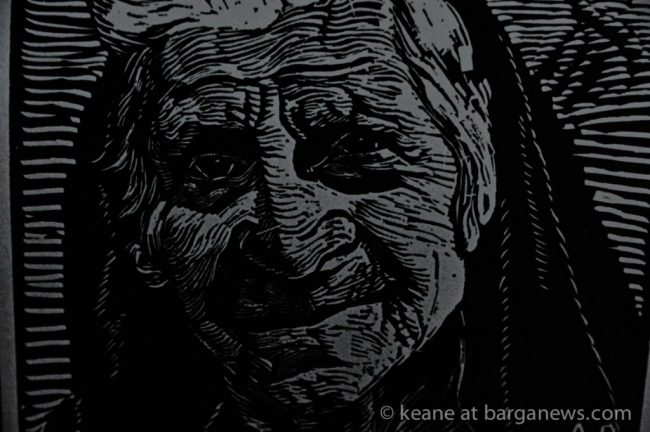

“This is what health looks like,” Pellegrini says, pointing to the weathered but immensely dignified face of Teresa Agostini, age 101, in a remarkable Balduini portrait from the turn of the last century. Agostini, who was also the subject of a Pascoli essay, was born and spent her life in Sommocolonia among the chestnuts, “in harmony with the Earth, eating lean foods,” says Pellegrini. “Sure, it was the only food her family could afford, but it also kept her going a very long time.”

Article by Frank Viviano – the 8 times Pulitzer Prize nominated journalist/ best selling author and barganews staff reporter

All articles by Frank Viviano can be seen here

|

|

|

|

Mostra di Angelo Pellegrini – La Chiesa del Santissimo Crocifisso, Barga Vecchia, 12 luglio – 31 agosto 2014

Da oltre mezzo secolo, Angelo Pellegrini ha vagato sulle creste apuane e nei prati appenninici della Garfagnana. Lungo le strade di montagna e i sentieri, ha scattato migliaia di fotografie suggestive, spesso poetiche, sia a colori che in bianco e nero. All’inizio del suo viaggio, ha trovato un mentore e un animo affine in Giovanni Pascoli – il cantore del mondo contadino, uno dei più celebri scrittori italiani dagli anni ’70 del 1800 alla sua morte nel 1912, e residente sulle colline di Castelvecchio di Barga. Gabriele D’Annunzio, contemporaneo e a volte rivale di Pascoli, lo descrisse come “l’ultimo figlio di Virgilio”, l’epico poeta e cantore della campagna pastorale italiana 2000 anni fa.

L’ammirazione di Pellegrini per Pascoli è lo sfondo di una mostra attualmente alla Chiesa del Santissimo Crocifisso, che si protrarrà fino al 31 agosto. “Si tratta di Giovanni Pascoli, non di me”, insiste. Ma in molteplici modi che Pascoli stesso avrebbe applaudito, la mostra è anche su Angelo Pellegrini: il suo personale attaccamento duraturo a un universo contadino che sta rapidamente scomparendo. “Siamo alla fine di un’epoca”, afferma.

Sotto il titolo “Cibo nella poesia e nella prosa di Giovanni Pascoli”, Pellegrini ha raccolto un’indagine di immagini e versi che fanno per quell’epoca ciò che Virgilio ha fatto per l’entroterra romano nel secolo finale prima di Cristo. La mostra è un poema esteso di per sé, combinando selezioni del lavoro fotografico di Pellegrini con le parole e le fotografie personali di Pascoli stesso, e riproduzioni di dipinti e incisioni dei noti artisti di Barga del periodo prebellico Adolfo Balduini, Alberto Magri e Umberto Vittorini.

Come suggerisce il titolo, il cibo è il principio organizzatore della mostra, così come lo è nel mondo contadino: il fulcro delle stagioni rurali, il legame essenziale tra il contadino e la terra. Pellegrini ha abbinato immagini avvincenti di questo mondo con le osservazioni di Pascoli – spesso nel dialetto dei suoi vicini contadini – sulla natura simbolica e pratica delle olive e del radicchio, del latte, delle cipolle e delle uova, tutti prodotti del suo giardino di Castelvecchio.

Ma nella Garfagnana, come Angelo Pellegrini e Giovanni Pascoli entrambi così memorabilmente ritraggono, il bosco di castagni primeggia su tutto il resto nella gerarchia del cibo. È casa dell’albero di pane, il nobile castagno. Il suo frutto ha fornito a innumerevoli generazioni la farina macinata usata per fare la polenta di castagne, così come il pane, la pasta di castagne e i deliziosi dolci di castagne conosciuti come neccio e castagnacci.

Purtroppo, è proprio questa caratteristica centrale del mondo contadino che sta diminuendo, come documentato da Pellegrini in fotografie di antichi mulini a grano di pietra e cascine abbandonate al degrado. “Ogni dettaglio che non è pietra – le porte, le travi del tetto, gli infissi, i mobili – è stato fatto a mano dal castagno”, dice. “Il castagno non solo nutriva i contadini, ma forniva anche le loro case e i loro letti”.

Oggi, il raccolto locale di castagne è una frazione minuscola di ciò che un tempo era. In parte, ciò è dovuto all’arrivo di un vespa parassita asiatica, “dryocosmus kuriphilus”, che ha decimato il raccolto di castagne negli ultimi anni. Ma il contesto più ampio è la scomparsa dell’agricoltura tradizionale dalle montagne, insieme all’ultima generazione di contadini le cui metodologie risalgono al tempo di Virgilio. I loro figli e nipoti sono emigrati a lavori moderni (e cibo moderno) nelle città italiane, e all’estero nel Regno Unito, nelle Americhe e in Australia.

“Questo è ciò che significa salute”, dice Pellegrini, indicando il volto consumato ma immensamente dignitoso di Teresa Agostini, di 101 anni, in un notevole ritratto di Balduini del turno del secolo scorso. Agostini, che fu anche oggetto di un saggio di Pascoli, nacque e visse a Sommocolonia tra i castagni, “in armonia con la Terra, mangiando cibi magri”, dice Pellegrini. “Certo, era l’unico cibo che la sua famiglia poteva permettersi, ma l’ha anche mantenuta in vita per molto tempo”.

Articolo di Frank Viviano

Tutti gli articoli di Frank Viviano possono essere visti qui.