Quite a few people have pointed out that the amount of articles on barganews.com have diminished somewhat over the past three months or so. We are still in the quieter winter season here in Barga so some of that reduced “noise” is logical but also at the same time those of you connected to social networks will have also noticed a dramatic increase in the amount of biroldo images being posted up from Barga …. and yes, the two are intricately connected.

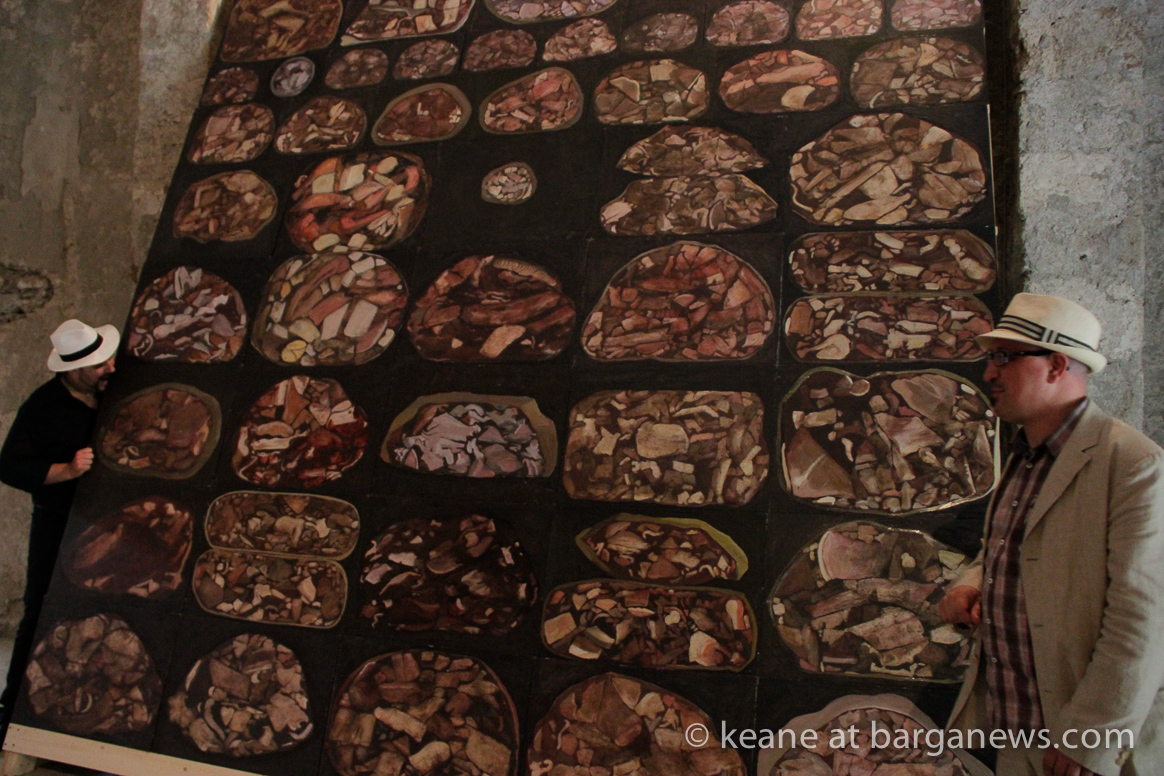

More or less for the whole of the winter Keane has been working in the studio on a series of paintings for a project which runs under the name of the #loveproject.

|

|

|

|

The #loveproject

More information will be published about the #loveproject later on this month but for the moment a brief description is that it is yet another collaboration between Keane and Fabrizio Da Prato and will be a series of 100 paintings which will be exhibited and will be on sale for just one weekend at Isola Santa, Garfagnana later on in the spring

The paintings will then be installed in five of the piazzas of five major Tuscan cities during the summer and people will be invited to take the paintings home free of charge as gifts from the artists to the public.

The aim of the project is to start a discussion about just what is the value of an artwork.

Will people still buy a painting at an exhibition knowing full well that the following day it can be obtained for free?

What is the value of a painting bought in a gallery – does it was have the same value if it is found on the street, given away or even stolen?

So what it is with the Biroldo ?

Biroldo – even the name is fascinating as it not really a local Italian word but a name that was probably brought down from the north of Europe as the Longobards expanded their territory into the south of Europe and founded the city of Barga over a thousand years ago. They brought with them their food which was heavily based on pigs

The Lombards or Langobards (Latin: Langobardī, Italian Longobardi), were a Germanic tribe who ruled Italy from 568 to 774.

I have been pondering the assertion that biroldo is of Nordic origin. It’s certainly true that all northern cultures include a pig’s blood pudding or blood sausage in their traditional winter diet, and in Europe “northern” almost always means derived from Scandinavian-Germanic origins. In this sense, the etymology of the word “biroldo” is obvious. While the linguistic construction “bl” is very rare in Latin, it is common in Germanic languages. When the Nordic-German Lombards brought their culinary traditions with them, they called the principal ingredient of the item in question “blood.” This root word is evident in almost all northern European languages: Old English blod from Proto-Germanic *blodam “blood” (cognates: Old Frisian blod, Old Saxon blôd, Old Norse bloð, Middle Dutch bloet, Dutch bloed, Old High German bluot, German Blut, Gothic bloþ), from “bhlo-to” perhaps meaning “to swell, gush, spurt.” This last reference, “bhlo-to,” is the most relevant, as it is very close to “biroldo” — and indeed, blood sausages do swell when cooked. The Latin-speakers of Tuscany adopted the sausage, but they wouldn’t have been able to pronounce its Nordic name. Hence the likely distortion of the syllable “bhlo” to “birol.” Somewhat analogous is the linguistic evolution of the Nordic word “blonden” to the Italian “bionda.” Most blond-haired Italians are, in fact, descendants of Nordic invaders who crossed the Alps after the 4th century A.D. – Frank Viviano

Biroldo è la prova che nulla viene sprecato quando si tratta di fare cibo dai maiali. Una volta che le salsicce, i prosciutti e i salami sono stati tutti preparati, ciò che resta, compresa la testa e il sangue, viene utilizzato per fare il tradizionale biroldo.

L’utilizzo del sangue come ingrediente integrale si può trovare in molte culture alimentari del nord Europa, conosciute con nomi diversi come salsiccia nera, ma qui in questa zona è una particolare ricetta e un particolare modo di preparazione che è unico per la Garfagnana e la Media Valle del Serchio.

È un cibo stagionale, poiché i maiali vengono generalmente macellati intorno al periodo di Natale e il biroldo è qualcosa che viene preparato e mangiato più o meno subito. Non è qualcosa che le persone amerebbero mangiare durante l’estate, ad esempio.

Il biroldo è anche conosciuto come il cibo che le persone odiano o amano.

Sembra che non ci sia una via di mezzo con le persone che vengono divise immediatamente in due campi distinti e opposti: o lo odiano o lo amano intensamente.

È quasi impossibile essere indifferenti al biroldo.

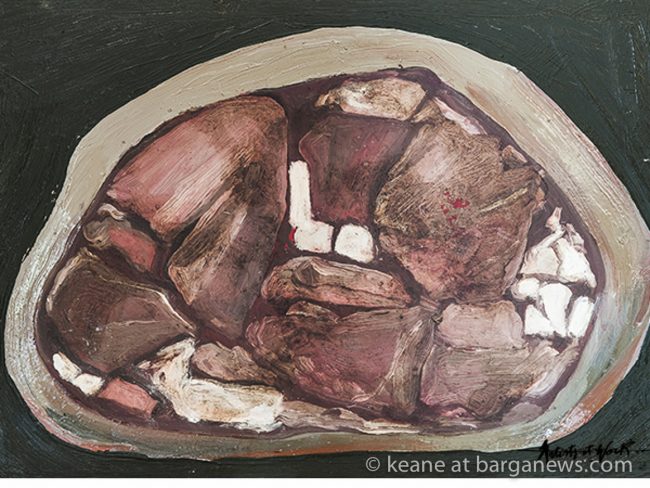

Biroldo is the proof that nothing is wasted when it comes to making food from pigs. Once the sausages, hams and salamis have all been prepared, what is leftover including the head and the blood is then used for making traditional biroldo.

The use of blood as an integral ingredient can be found in many northern European food cultures, known under different names such as black sausage but here in this area it is a particular recipe and a particular way of preparing that is singular to Garfagnana and Media Valle Del Serchio.

It is a seasonally food as the pigs are generally slaughtered around Christmas time and biroldo is something which is prepared and eaten more or less straight away. It is not something that people would enjoy eating during the summer for instance.

Biroldo is also known as the food which people either hate or love.

There seems to be no middle ground with people being divided straight away into two distinct and opposing camps – they either hate it or love it intensely.

It is almost impossible to be indifferent about biroldo.

Probabilmente il termine è arrivato con i Longobardi (Lucca era la loro capitale Toscana)

biroldo = insaccato di maiale riempito di sangue e altri ingredienti. E’ ritenuta voce di probabile origine germanica da Giacomo Devoto (“Avviamento all’etimologia italiana”)Biroldo della Garfagnana Toscana

Il Biroldo della Garfagnana è un salume dalle origini molto antiche, il cui nome sembra derivare dall’epoca longobarda. Un salume tipico della Garfagnana realizzato con le parti meno nobili del maiale, come la testa, il cuore e lingua, che vengono tagliate e bollite, conciate con sale e spezie amalgamate con il sangue del maiale ed insaccate nello stomaco dello stesso…

Molti rabbrividiranno ed effettivamente non è il solito triste prosciutto cotto, è molto più gustoso, saporito e prelibato, tanto da essere entrato di diritto nel paniere dei prodotti tipici lucchesi ed è diventato un Presidio SlowFood…

Le spezie usate per la concia sono il finocchio selvatico, il sale, il pepe, la noce moscata, i chiodi di garofano, la cannella, l’anice stellato e l’aglio, ma non i pinoli che invece caratterizzano il biroldo lucchese…

In linea con l’animo campanilistico e conservatore dei toscani, non sono note le percentuali usate delle spezie, che diventano un segreto custodito tra padri e figli norcini, facendo sì che non esisterà mai un biroldo uguale all’altro…

Prodotto più frequentemente in inverno, non ha una lunga conservazione, pertanto viene consumato entro quindici giorni dalla preparazione, tagliato a striscioline sottili, magari accompagnato dal pane di patate o dal pane di neccio…

Sebbene la preparazione di questo insaccato faccia pensare a sapori forti ed intensi, in bocca è morbido e delicato dal gusto equilibrato e persistente…

Per fare questo particolare e antico sanguinaccio si utilizza esclusivamente la testa del maiale, che è più magra e conferisce una consistenza morbida al prodotto, con l’unica eccezione di cuore e lingua. Le spezie che profumano l’impasto di carne e sangue possono variare, ma sono tassativamente esclusi i pinoli che, spesso, caratterizzano invece il biroldo di Lucca.

La ricetta non è complicata, ma occorre una grande manualità e un saper fare attento per ottenere il prodotto giusto (tradizionalmente è compito delle donne). Si fa bollire la testa del maiale per tre ore, la si disossa accuratamente e si unisce una piccola quantità di sangue, aggiungendo via via la spezie: spezie toscane, con una prevalenza del finocchio selvatico. Naturalmente ci sono anche sale e pepe, accompagnati da noce moscata, chiodi di garofano, cannella e anice stellato – le quantità cambiano in funzione della mano e del gusto del norcino – e c’è chi ci aggiunge pure un po’ di aglio.

Ottenuto l’impasto di carne, sangue e spezie, lo si insacca: prima di essere consumato, deve bollire per altre tre ore e raffreddarsi lentamente all’aria, sotto la pressione di un peso, perdendo così la parte più grassa.

Il biroldo si consuma tagliato a striscioline alte un centimetro entro quindici giorni dalla produzione, magari accompagnato dal tipico pane di castagne garfagnine o dal pane di patate. In bocca è morbido e il suo gusto è perfettamente equilibrato: sangue e spezie non prevaricano il sapore della carne magra della testa del maiale, ma gli conferiscono sentori delicati e persistenti. – source