On a balmy summer evening at poolside, the Villa Moorings played host Monday to the brain trust of Garfagnana history before an overflow audience. The subject was the imposing Duomo di Barga, a monument that has few peers in its distinctive architecture – and more intriguingly, in the array of mysteries that surround its origins and its patron saint.

On a balmy summer evening at poolside, the Villa Moorings played host Monday to the brain trust of Garfagnana history before an overflow audience. The subject was the imposing Duomo di Barga, a monument that has few peers in its distinctive architecture – and more intriguingly, in the array of mysteries that surround its origins and its patron saint.

Not the least of those mysteries are links associating the Duomo with ancient spiritual cults in the Fertile Crescent kingdoms of Egypt, Syria and Mesopotamia, the cradle of civilization.

The speakers included Antonio Nardini, the prolific dean of local historians; the eminent professor and Barghigiano native son Stefano Borsi of the University of Naples; Pier Giuliano Cecchi, whose painstaking archival research is regularly featured on barganews; and the two erudite Marroni brothers, Pier Carlo and Gian Carlo. Among them, they have published dozens of books, monographs and scholarly articles chronicling the town’s long and complex life.

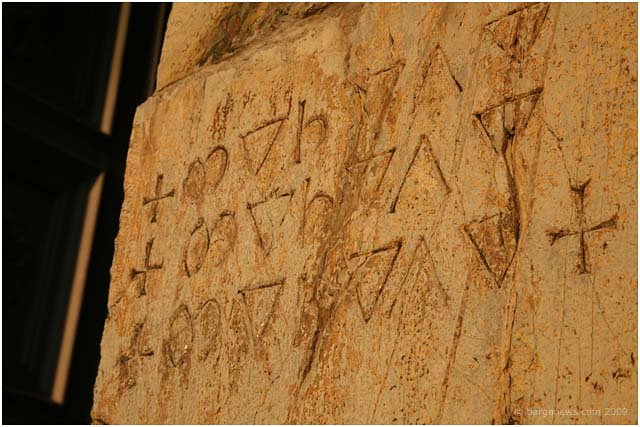

As Professor Borsi points out in his authoritative “Le Origini di Barga e il culto di San Cristoforo” (Libria 2009), very few documents survive from the founding and early development of the Duomo, which obliges scholars to reconstruct its chronology through speculative interpretation of architectural peculiarities and decorative motifs. Their studies focus on such details as iconic crosses and serpent statues, as well as the strange inscription carved into the façade of the western entrance, rendered in letters that appear to draw on several pre-Medieval alphabets.

In the view of both Cecchi and Pier Carlo Marroni, the crosses and other symbols, many of which are engraved in no obvious pattern on the exterior walls, imply that the Duomo was once a bastion of the Knights Templar. A militant order of priests and soldiers, the Templars built churches and fortresses all over the Holy Land and eastern Anatolia, amassing enormous political power and wealth in the epoch of the Crusades. Eventually, they fell out with the Vatican, and were disbanded in the 14th century, with many of their leaders accused of heresy and burned at the stake.

The accusations, as well as continuing modern fascination with the Templars – whose exploits and arcane rituals have fostered an entire genre of fiction – lead inevitably to the Levantine shores where heresy and pre-Christian mysticism abounded, and where the order was once a kingdom in its own right.

The Duomo’s suggestive connections to the near-east, however, are of far older lineage than the Crusades. The tale of its principal patron, San Cristoforo, is shrouded in fable and often explained as a Christian adaptation of Teutonic forest mythology. But its more likely roots, tantalizingly suggested in the Duomo’s serpentine statuary, lie in the esoteric snake cults of Egypt and Anatolia that Roman legions encountered (and often embraced) in their military campaigns across the Mediterranean among the Berbers, Kurds and Armenians nearly 2,000 years ago.

The Duomo’s suggestive connections to the near-east, however, are of far older lineage than the Crusades. The tale of its principal patron, San Cristoforo, is shrouded in fable and often explained as a Christian adaptation of Teutonic forest mythology. But its more likely roots, tantalizingly suggested in the Duomo’s serpentine statuary, lie in the esoteric snake cults of Egypt and Anatolia that Roman legions encountered (and often embraced) in their military campaigns across the Mediterranean among the Berbers, Kurds and Armenians nearly 2,000 years ago.

There is evidence that a real San Cristoforo was arrested for preaching the new religion of Christianity in this very region during the third century, and was beheaded on the Anatolian coast around 250 A.D.

Ultimately, Pier Carlo Marroni observed, the mysterious symbols in Barga’s church date back much further, to the Anatolian Hittites of 1700 BC, who carved serpents “that could have been photocopies of those found in the Duomo.”

As for the odd inscription at the Duomo’s western entrance, which vagely appears to read “+Mihili +Mihili +Mihili, Pier Giuliano Cecchi believes it may be an invocation of San Michele, protector of the universal Catholic Church. But Stefano Borsi takes a decidedly unromantic view of its curious jumble of Greek , Latin and unidentifiable letters. The explanation, he says, is probably not another mystery, but “simply a priest who was not as literate as he pretended when he supervised the engraving.”

As for the odd inscription at the Duomo’s western entrance, which vagely appears to read “+Mihili +Mihili +Mihili, Pier Giuliano Cecchi believes it may be an invocation of San Michele, protector of the universal Catholic Church. But Stefano Borsi takes a decidedly unromantic view of its curious jumble of Greek , Latin and unidentifiable letters. The explanation, he says, is probably not another mystery, but “simply a priest who was not as literate as he pretended when he supervised the engraving.”

Article by Frank Viviano