There are few, if any, churches in Western Europe to rival Barga’s Duomo for sheer provocative mystery. From its near-cubist architecture to its peculiar relationship with a distant mountain arch, the great marble edifice overlooking the Serchio Valley is an encyclopedia of questions that yield few unambiguous answers.

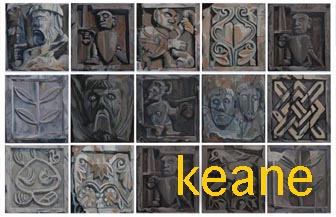

Now comes the painter Keane, who has been documenting Barga’s daily life and rich past for two decades, with 52 canvases that profoundly deepen the mystery. They draw on 212 extraordinary bas-reliefs, mounted so high on the outer parapets of the edifice that passersby and parishioners alike seldom notice them. The age of the sculptures, their provenance, their creators — indeed their very purpose and intention — are all unknown.

In a sense, they relate a hidden chronicle in full light, a narrative that defies precise definition but invites the sort of imaginative speculation that often yields more essential truth than the dry facts of pure documentation. “None of this work is simply decorative,” Keane says of the Duomo carvings. “The more I studied it, searching to understand what it meant, the more potent it was for me.”

What lies at the crux of Keane’s own fascination with the walls of the Duomo, the saga that emerges from his paintings and their venerable subject, is one of history’s great transitional moments. Peering out from their airy niches, human figures, animals and symbolic floral designs invoke a lost world in which Central Italy was neither obstinately pagan in the waning sense of its Greco-Roman and Etruscan origins, nor fully Christian as it would become by the 12th century. They blend both of these currents with far more ancient local folk traditions, and powerful allusions to the gods of Norse-Germanic Lombard invaders who descended on the Serchio Valley 1,500 years ago and gradually displaced its Latin ruling class.

An archer, hair flung back in the frenzy of the chase , sends an arrow across the void from one relief to another, and into the neck of an enormous bird perched heavily atop groaning trees. Enigmatic moon-faced warriors, dragons, bulls’ heads, serpents and snarling serpent-tailed dogs fill adjoining panels, writhing in fury or gazing ominously forward. Set among them, in prolific array, are abstract interpretations of flowers and foliage — most frequently geometric trees. No inscription accompanies them; they speak wordlessly in an archaic iconic language.

What does it say? We can only guess. But what seems inescapable is that the tale is far older than the date of origin commonly ascribed to Duomo, sometime in the 10th century. At the very least, the iconic narrative bespeaks a counter-current in the annals of this city and its surrounding region, a submerged collective memory.

At least one clue to its meaning may lie in the Duomo’s unique and distinctly unusual orientation. Catholic churches, in accordance with 2,000 years of liturgical tradition, are aligned along an east-west axis, so that priest and parishioners will pray facing toward the rising sun, symbolically alluding to Christ’s resurrection. The Duomo is not merely off axis, but seems precisely “aimed” at a giant natural arch on Monte Forato across the valley in the Apuan Alps. Twice per year, as observed from the main Duomo portal, the sun appears to set twice — the doppio tramonto — first above the Apuan ridgeline, then reappearing in a concentrated stream of light through the Monte Forato arch, where it sets once again. Even today, Barghigiani gather before the Duomo to watch the doppio tramonto, a ritual that may date back more than 3,000 years to a time when the area was inhabited by sun-worshipping Liguri tribesmen, who may have built a temple on the very site of the present church.

The sunset-fixed orientation suggests that this church, more than any other that comes to mind, has visibly absorbed both pre-Roman and pre-Christian beliefs and customs into its Christian identity. What Keane argues, in his representative selection, is that the synthesis is repeated in its exterior ornamentation. The familiar Greco-Roman and Mediterranean motifs of most Italian religious structures give way to figures borrowed almost directly from prehistoric carved granite steles found across the Garfagnana and Lunigiana regions. Pay a visit to the remarkable archeology museum in Pontremoli, on the Magra River north of Aulla, and you will encounter the cousins of those moon-faced Duomo warriors among ancestors of the Liguri, believed to have been related to the Celts — who inhabited what is now the Province of Lucca a thousand years before the Roman Republic. You will also see the same intricate Celtic “Solomon’s knot” that is one of the Duomo’s most prominent abstract designs.

Travel 2,500 km further north, to the Universitets Historiska Museum in Lund, Sweden, and you stand among stone pillars that depict the “tree of life,” a central symbol of Nordic and Lombard mythology, executed almost precisely as it is in Keane’s Duomo canvases. You will also meet a flowing-haired bowman: he is Ull, the charismatic god of archers and hunters. As for the Duomo archer’s target in an adjoining niche, it is tempting to imagine that he is Hraesvelg, a malevolent Nordic deity known as the “corpse swallower,” who often takes the form of a huge bird.

Article by the 8 times Pulitzer Prize nominated journalist/ best selling author and barganews staff reporter Frank Viviano

|

|

|

|

Ci sono pochi, se non nessuna, chiese in Europa occidentale che possono competere con il Duomo di Barga per un’enigmatica provocazione. Dalla sua architettura quasi cubista al suo rapporto particolare con un arco di montagna lontano, l’imponente edificio in marmo che sovrasta la valle del Serchio è un’enciclopedia di domande che forniscono pochi risposte inequivocabili.

Ora arriva il pittore Keane, che ha documentato la vita quotidiana e la ricca storia di Barga per due decenni, con 52 tele che approfondiscono profondamente il mistero. Essi si basano su 212 straordinari bassorilievi, montati così in alto sui parapetti esterni dell’edificio che i passanti e i parrocchiani raramente li notano. L’età delle sculture, la loro provenienza, i loro creatori, infatti il loro stesso scopo e intenzione, sono tutti sconosciuti.

In un certo senso, essi raccontano una cronaca nascosta alla luce, una narrazione che sfida una definizione precisa ma invita alla speculazione immaginativa che spesso fornisce una verità essenziale più dei fatti secchi della pura documentazione. “Nessuno di questo lavoro è semplicemente decorativo”, dice Keane delle sculture del Duomo. “Più studiavo, cercando di capire cosa significasse, più potente era per me”.

Ciò che si trova alla base della fascinazione di Keane per le mura del Duomo, la saga che emerge dalle sue tele e il loro rispettabile soggetto, è uno dei grandi momenti di transizione della storia. Guardando fuori dalle loro nicchie ariose, figure umane, animali e disegni floreali simbolici evocano un mondo perduto in cui il centro Italia non era ostinatamente pagano nella sua accezione in declino delle sue origini greco-romane ed etrusche, né completamente cristiano come sarebbe diventato entro il 12 ° secolo. Essi fondono entrambi questi correnti con tradizioni folk locali molto più antiche e allusioni potenti agli dei degli invasori nordico-germanici Lombardi che scesero nella valle del Serchio 1.500 anni fa e gradualmente sostituirono la sua classe dominante latina.

Un arciere, i capelli scagliati indietro nella frenesia della caccia, manda una freccia attraverso il vuoto da un rilievo all’altro e nel collo di un uccello enorme posato pesantemente su alberi gementi. Guerrieri enigmatici dal volto di luna, draghi, teste di tori, serpenti e cani ringhianti con code di serpenti riempiono i pannelli adiacenti, contorcendosi in furia o guardando minacciosamente in avanti. Tra di loro, in abbondanza, ci sono interpretazioni astratte di fiori e foglie, spesso alberi geometrici. Nessuna iscrizione li accompagna; parlano in una lingua iconica arcaica senza parole.

Cosa dice? Possiamo solo indovinare. Ma ciò che sembra innegabile è che la storia è molto più vecchia della data di origine comunemente attribuita al Duomo, in qualche momento del 10 ° secolo. Almeno, la narrazione iconica testimonia una controcorrente negli annali di questa città e della sua regione circostante, una memoria collettiva sommersa.

Almeno un indizio per il suo significato potrebbe trovarsi nell’orientamento unico e decisamente insolito del Duomo. Le chiese cattoliche, in conformità con la tradizione liturgica di 2.000 anni, sono allineate lungo un asse est-ovest, in modo che il prete e i fedeli preghino rivolti verso il sole che sorge, alludendo simbolicamente alla risurrezione di Cristo. Il Duomo non è solo fuori asse, ma sembra essere precisamente “puntato” verso un arco naturale gigante su Monte Forato attraverso la valle nelle Alpi Apuane. Due volte all’anno, come osservato dal portale principale del Duomo, il sole sembra tramontare due volte – il doppio tramonto – prima sopra la cresta delle Alpi Apuane, quindi riapparendo in un flusso di luce concentrato attraverso l’arco di Monte Forato, dove tramonta di nuovo. Ancora oggi, i Barghigiani si riuniscono davanti al Duomo per guardare il doppio tramonto, un rituale che potrebbe risalire a più di 3.000 anni fa, quando l’area era abitata da tribù liguri adoratrici del sole, che potrebbero aver costruito un tempio proprio sul sito della chiesa attuale.

L’orientamento fisso al tramonto suggerisce che questa chiesa, più di ogni altra che viene in mente, ha assorbito chiaramente sia le credenze e le usanze pre-romane che quelle pre-cristiane nella sua identità cristiana. Ciò che Keane sostiene, nella sua selezione rappresentativa, è che la sintesi si ripete nella sua ornamentazione esterna. I motivi familiari greco-romani e mediterranei delle maggiori strutture religiose italiane cedono il passo a figure prese quasi direttamente dalle stele scolpite preistoriche trovate in tutte le regioni della Garfagnana e della Lunigiana. Visita il notevole museo di archeologia a Pontremoli, sul fiume Magra a nord di Aulla, e incontrerai i cugini di quei guerrieri con la faccia di luna del Duomo tra gli antenati dei Liguri, che si crede fossero imparentati con i Celti – che abitavano ciò che oggi è la Provincia di Lucca mille anni prima della Repubblica Romana. Vedrai anche lo stesso intricato disegno astratto “nodo di Salomone” celtico che è uno dei più prominenti del Duomo.

Viaggia 2.500 km più a nord, al Museo Storico Universitario di Lund, in Svezia, e ti troverai tra pilastri di pietra che raffigurano l’ “albero della vita”, un simbolo centrale della mitologia nordica e longobarda, eseguito quasi esattamente come nei dipinti del Duomo di Keane. Incontrerai anche un arciere con capelli fluenti: è Ull, il carismatico dio degli arcieri e degli cacciatori. Per quanto riguarda il bersaglio dell’arciere del Duomo in una nicchia adiacente, è tentato di immaginare che sia Hraesvelg, una divinità nordica malvagia conosciuta come il “divoratore di cadaveri”, che spesso assume la forma di un grande uccello.

Articolo di Frank Viviano the 8 times Pulitzer Prize nominated journalist/ best selling author and barganews staff reporter Frank Viviano

I wish I could figure out how to comment by using my Beauly log in, (maybe I have?).. but anyway …

I forwarded this article on to a friend (from Sofia, Bulgaria) who has been living in St. John’s Newfoundland as an artist for 20 plus years.. He, and his (artist as well) wife, have not yet been to Barga, but they are now restoring a place in the very very Southern tip of Sicily.. anyway.. his thoughts back to me after viewing and reading this article I shared with him recently…

“very, very interesting. Not only did I like the paintings (actually, a lot; for their simplicity, honesty, expressiveness and unpretentiousness), but I was also rather impressed by the article. I looked carefully at the paintings and read the article twice just to make sure I was not responding in a biased way (for obvious reasons). Then I checked out Frank Viviano and, no wonder, I found out that he was an illustrious journalist with serious credentials. Barga should be very proud to count two individuals of that calibre among its citizens! Thanks a lot for sharing, it makes me wanna go to Barga, which I know, we will do in the not too distant future.” Luben Boykov http://lubenboykov.com/

There you go…

Cheers,

Beauly