What is it about Barga and art? What accounts for its enormously disproportionate creative community? The inspiration of its sublime natural setting? Its evocative history, landmarked by the ornate palaces and churches along its cobbled streets? Or did some mysterious, empowering tide animate the poetry of Giovanni Pascoli and the painterly genius of Cordati, Magri, Balduini and Vittorini at the end of the 19th century — embracing music a few decades later and surging onward into the 21st century?

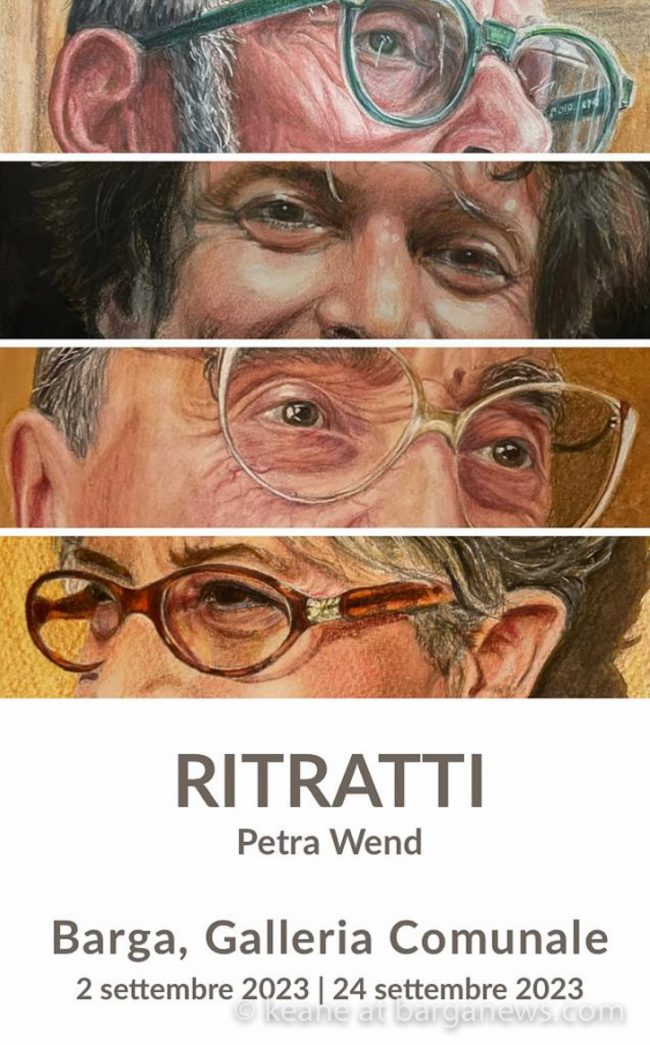

There is no persuasive answer, but the phenomenon itself is unmistakable, documented today in a brilliant cast of musicians and composers, photographers and painters at work in this small town of less than 10,000 on the western flank of the Apennines. The latest example is Petra Wend: born in Germany, risen to the heights of academic distinction in the United Kingdom, settled in what she refers to as ”half-retirement” in Barga — and revealed almost overnight as a portrait painter of rare technical skill and emotional power.

That she has completed (at last count) almost 200 finished works would be surprising under any circumstances, much less with the subtlety commanded by Wend. But the fact that she undertook the very first of those portraits a scant three years ago — with almost no formal training apart from a beginner’s course with local artist Christ Bell, during Barga’s pandemic lockdown in the winter of 2020 — is nothing short of astounding.

Her remarkable talent is now on display at the Galleria Comunale on Via del Borgo in the Centro Storico, just steps away from the gallery of André Romijn, a Dutch citizen who took to his own easel after settling in Barga in 2018 and became a portraitist.

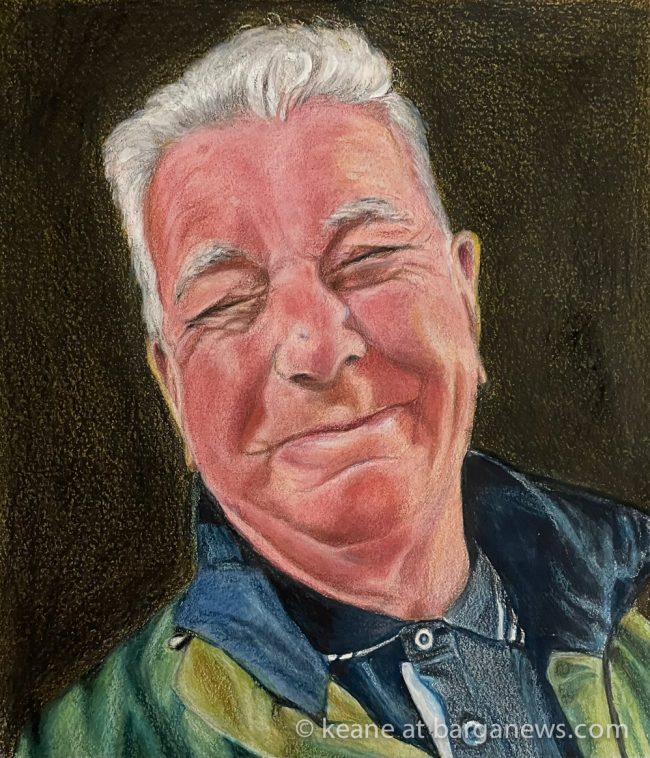

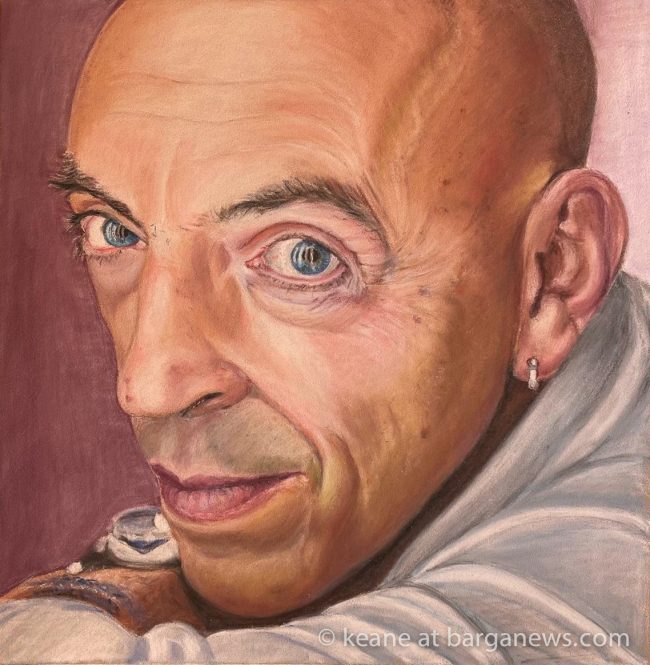

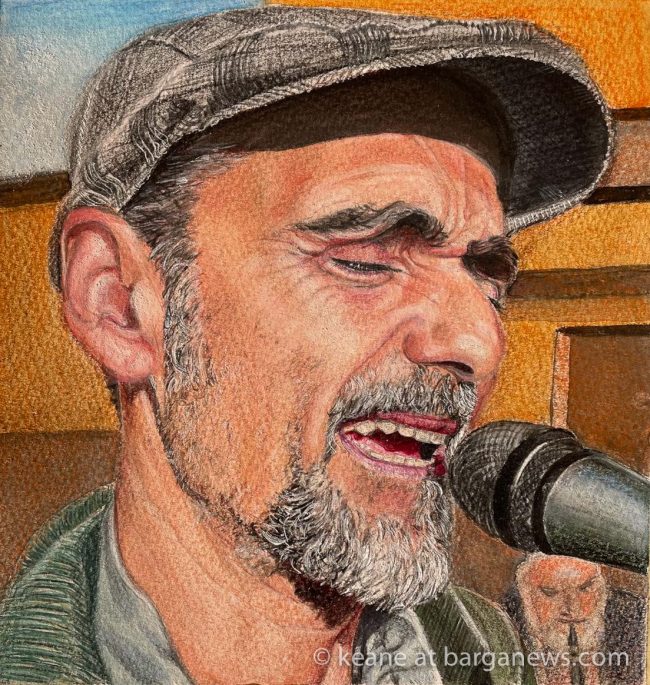

The mostra concentrates on Petra Wend’s contemporary Barga neighbors, among them a rich sampling of her fellow artists and musicians, along with notable characters from the open-air theater of life in the town’s atmospheric center. All of them are immediately recognizable, and not simply because Wend is gifted with a marvelous ability to capture likeness. Far more important, she has an acute sensitivity to what lies below a subject’s public guise: character, personality, shadows of doubt and bright currents of pure infectious joy. “It’s all in the seeing, the observing,” she says, as though perceptive insight was a common tool that everyone might all employ if they just gave it a try.

The marriage of technical prowess and intense observation has evolved into a distinctive Petra Wend style. “I like vibrant colors,” she says, “light and dark contrasts, close details and thin brush strokes.” It is in those details and brush strokes that the near-photographic likenesses of her subjects are achieved. But the more subtle Wendisms — her attention to deeper, movingly human peculiarities that lie under the surface — are rendered in the interplay of color and contrast.

They are heirs to a tradition as old as civilization. Realistic portraiture dates back to Imperial Rome 2,000 years ago and Pharaonic Egypt a millennium earlier. In the famous painted bust of Queen Nefertiti (1370 BC) and the Tusculum sculpture of Julius Caesar (50 BC), two of ancient history’s most imposing celebrities are vividly alive and coldly intimidating. Portraits in their eras bespoke the narcissism of unlimited power, a far cry from the world of Petra Wend, who was born in the grim ruins of World War II and raised in the working class home of a type-setter.

Yet she felt the tug of painterly ambition very early, and applied to enter a German art school for promising children. What ensued was one of the few setbacks in an otherwise immensely successful professional life. The school rejected her application. Her family wasn’t the sort that produced artists.

Instead, Wend followed what would appear to be a very different career path. She studied Italian and French at the University of Münster, then went on to acquire a doctorate in Italian language and literature at Britain’s University of Leeds in 1990. Two decades later she had risen to the post of principal and vice-chancellor at Queen Margaret University in Edinburgh, where she remained until her move to Barga.

It was an exemplary journey for the little girl who deeply yearned to paint, only to be refused any training, but perhaps not the numbing detour it seems. In Wend’s own view, her academic career was also a running education — indeed an immersion — in 15th and 16th century European culture. The title of Wend’s thesis at Leeds, “The Female Voice: Lyrical Expression in the Writings of five Italian Renaissance Poets,” tells the tale.

Not incidentally, it was precisely in those two centuries that portraiture expanded its horizons beyond cold power to the universe of “ordinary” humanity in all of its extra-ordinary diversity. The enigmatic, heart-wrenching smile of Mona Lisa, Leonardo da Vinci’s “La Gioconda,” replaced the frigid gaze of Nefertiti and Caesar.

Her painterly persona today, Petra Wend asserts — her own absorption with sorrows and joys of the human condition — “is absolutely grounded in my studies of the Renaissance.”

Article by staff reporter of barganews, Frank Viviano, a journalist nominated 8 times for the Pulitzer Prize and bestselling author. All of Frank Viviano’s articles on barganews can be viewed here.

|

|

|

|

Cosa c’è di così speciale riguardo a Barga e l’arte? Cosa spiega la sua comunità creativa enormemente sproporzionata? L’ispirazione del suo sublime contesto naturale? La sua evocativa storia, segnata dai sontuosi palazzi e dalle chiese lungo le sue strade acciottolate? O forse qualche misteriosa e potente forza ha animato la poesia di Giovanni Pascoli e il genio pittorico di Cordati, Magri, Balduini e Vittorini alla fine del XIX secolo, abbracciando la musica qualche decennio dopo e proseguendo nel XXI secolo?

Non esiste una risposta convincente, ma il fenomeno stesso è inequivocabile, documentato oggi in un brillante gruppo di musicisti e compositori, fotografi e pittori che lavorano in questa piccola città di meno di 10.000 abitanti sul versante occidentale degli Appennini. L’ultimo esempio è Petra Wend: nata in Germania, salita alle vette della distinzione accademica nel Regno Unito, stabilitasi in quella che lei definisce “mezza pensione” a Barga e rivelatasi quasi da un giorno all’altro come una ritrattista di rara abilità tecnica e potere emotivo.

Il fatto che abbia completato (all’ultima conta) quasi 200 opere finite sarebbe sorprendente in qualsiasi circostanza, figuriamoci con la delicatezza di cui Petra Wend è capace. Ma il fatto che abbia intrapreso il suo primo ritratto appena tre anni fa, con quasi nessuna formazione formale se non un corso per principianti con l’artista locale Christ Bell, durante il lockdown pandemico di Barga nell’inverno del 2020, è davvero straordinario.

Il suo notevole talento è ora in mostra alla Galleria Comunale in Via del Borgo nel Centro Storico, a pochi passi dalla galleria di André Romijn, un cittadino olandese che si è dedicato alla sua stessa tavolozza dopo essersi stabilito a Barga nel 2018 e diventato un ritrattista.

La mostra si concentra sui contemporanei di Barga di Petra Wend, tra cui un ricco campione dei suoi colleghi artisti e musicisti, insieme a personaggi notevoli dal teatro all’aperto della vita nel centro suggestivo della città. Tutti loro sono immediatamente riconoscibili, e non solo perché Wend è dotata di una meravigliosa capacità di catturare la somiglianza. Molto più importante, ha una sensibilità acuta per ciò che si cela dietro l’aspetto pubblico di un soggetto: carattere, personalità, ombre di dubbio e brillanti correnti di pura gioia contagiosa. “È tutto nel vedere, nell’osservare”, dice, come se l’acume percettivo fosse uno strumento comune che tutti potrebbero utilizzare se solo ci provassero.

Il matrimonio tra abilità tecnica e intensa osservazione si è evoluto in uno stile distintivo di Petra Wend. “Mi piacciono i colori vibranti”, afferma, “i contrasti tra luce e ombra, i dettagli ravvicinati e i tratti sottili del pennello.” È in quei dettagli e tratti di pennello che si raggiungono le somiglianze quasi fotografiche dei suoi soggetti. Ma le Wendismi più sottili, la sua attenzione alle peculiarità umane più profonde e commoventi che si nascondono sotto la superficie, sono rappresentati dall’interazione di colore e contrasto.

Sono eredi di una tradizione antica quanto la civiltà stessa. Il ritratto realistico risale all’Impero Romano, 2000 anni fa, e all’Egitto faraonico un millennio prima. Nel famoso busto dipinto della Regina Nefertiti (1370 a.C.) e nella scultura tuscolana di Giulio Cesare (50 a.C.), due delle celebrità più imponenti della storia antica sono vividamente vivi e freddamente intimidatori. I ritratti delle loro epoche riflettevano il narcisismo del potere illimitato, ben lontano dal mondo di Petra Wend, nata nelle grigie rovine della Seconda Guerra Mondiale e cresciuta in una casa della classe lavoratrice.

Tuttavia, ha sentito il richiamo dell’ambizione pittorica molto presto, e ha cercato di entrare in una scuola d’arte tedesca per bambini promettenti. Ciò che ne è conseguito è stato uno dei pochi ostacoli in una vita professionale altrimenti immensamente riuscita. La scuola ha respinto la sua domanda. La sua famiglia non era del tipo che produce artisti.

Invece, Wend ha seguito ciò che sembrerebbe essere un percorso di carriera molto diverso. Ha studiato italiano e francese all’Università di Münster, poi ha conseguito un dottorato in lingua e letteratura italiana presso l’Università di Leeds in Gran Bretagna nel 1990. Due decenni dopo, era arrivata alla carica di preside e vice-cancelliere alla Queen Margaret University di Edimburgo, dove è rimasta fino al suo trasferimento a Barga.

È stato un viaggio esemplare per la bambina che desiderava ardentemente dipingere, solo per essere rifiutata nella sua formazione, ma forse non è stata la deviazione anestetizzante che sembra. Nella visione di Wend, la sua carriera accademica è stata anche un’educazione in corso – anzi, un’immersione – nella cultura europea del XV e XVI secolo. Il titolo della tesi di Wend a Leeds, “La Voce Femminile: Espressione Lirica nei Testi di Cinque Poeti Italiani del Rinascimento”, racconta la storia.

Non incidentalmente, è stato proprio in quei due secoli che il ritratto ha ampliato i suoi orizzonti al di là del potere freddo verso l’universo della “ordinaria” umanità in tutta la sua straordinaria diversità. Il sorriso enigmatico e straziante della Gioconda, opera di Leonardo da Vinci, ha sostituito lo sguardo freddo di Nefertiti e Cesare.

La sua personalità pittorica oggi, afferma Petra Wend – la sua stessa affinità con le tristezze e le gioie della condizione umana – “è assolutamente radicata nei miei studi sul Rinascimento.”

Articolo dello staff del reporter di barganews, Frank Viviano, un giornalista nominato 8 volte per il Premio Pulitzer e autore di bestseller. Tutti gli articoli di Frank Viviano su barganews possono essere visualizzati qui.