Swietlan “Nick” Kraczyna (March 24, 1940 – February 1, 2026)

Swietlan “Nick” Kraczyna, a key figure in postwar art on both sides of the Atlantic, passed away at his country home near Florence on February 1. His wife, Sylvia Hetzel, was at his side.

To a remarkable degree, he was a conscious heir to the intellectual and creative legacy of the Italian Renaissance. For half a century, his years were divided between Barga’s atmospheric historic center — immortalized in his most famous work — and the Florentine hamlet where the 15th century painter Domenico Ghirlandaio served as Michelangelo’s master.

As a teacher in his own right, Kraczyna had a rare ability to connect the past tangibly with the present, in conversations that often ranged across a dizzying span of literature, history and science. Yet at the same time, his inner gaze remained trained on the shadowy dreamlife of the visible world: universal archetypes, framed in ancient myth and legend, that wield hidden power in the collective memory of humanity.

Ecstatic moments were often central to Kraczyna’s exploration of that realm, whether in the form of sensuous eroticism or its metaphoric sibling, the heady rush of artistic creativity. His musings on the act of creation fueled decades of work based on the myth of Icarus, the Greek embodiment of imaginative risk, whose doomed flight on feathered wings held together by wax — and fatally melted by the sun — is at once a warning and an irresistible spur. For Kraczyna, Icarus was a precursor to Shakespeare’s ecstatic fantasies in “Midsummer’s Night Dream, ” and the hallucinatory spectacle of carnivals. They are the favored stage of Harlequin, the masked comic deceiver, who romps and dances through Kraczyna homages to the music of his fellow Russians, Igor Stravinsky and Peter Tschaikovsky.

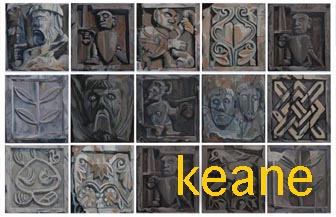

Similar themes and protagonists occupied much of Kraczyna’s prolific output as an engraver, alternating with excursions into photography and pictorial landscape. The best-known example is his iconic portrait of Barga, a masterpiece of color and composition. The town is rendered as an imaginary family in stone and brick, its millennial Duomo a protective parent standing watch over a walled brood of houses gazing with hope and anxiety into the countryside beyond.

The same timeless ambiguity haunts his celebrated photograph of Florentines crowded into a fragile skiff so narrow that it offers only standing room, caught in the raging flood waters of the River Arno in 1966. It is among the most powerful documentary images of the 20th century, a stark depiction of 10 stunned men and women suddenly transformed into refugees from their ordinary roles as shopkeepers, clerks, students and workers.

In this respect, the photo marks an implicit passage into autobiography. Kraczyna was born in the cataclysmic spring of 1940 to ethnic Russian parents in Poland, reeling from simultaneous invasion by the Nazi Wehrmacht and the Soviet Red Army. The setting of his earliest memories is the utter destruction of hundreds of cities and towns, and the darkest passages of the Holocaust. In 1945, after fleeing across a thousand devastated kilometres, often under deadly fire, the Kraczyna family was interred in a postwar refugee camp.

Swietlan Nicholas Kraczyna was 11 years old, in 1951, when a religious charity sponsored his family’s relocation to America. In 1962, he completed a degree in painting at the prestigious Rhode Island School of Design, and taught at Southern Illinois University until 1964, when he and his young wife, Amy Luckenbach, moved permanently to Tuscany. Luckenbach, a renowned puppeteer, passed away in 2009.

In addition to his accomplishments as an artist, Nick Kraczyna was revered for his engraving workshops — focused on his own widely influential multi-plate color etching techniques — which attracted students from all over the world. They included such luminaries as Argentina-born Gabriel Feld, former dean of Architecture at the Rhode Island School of Design, and the American artist Maya Hardin, whose works have been prominently featured by New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In 1970 Kraczyna was one of ten artists chosen to represent the United States in Florence’s Palazzo Strozzi Biennale di Grafica. He taught courses at universities and art schools in the United States, England, Italy, Mexico and Colombia, and his etchings are in the permanent collections of Florence’s Uffizi Gallery and countless other museums. He co-authored “I Segni Incisi” , the first Italian comprehensive textbook on the history and techniques of etching.

In addition to his wife, he is survived by his three children, Anna, Anatol and Emma, and five grandchildren.

Swietlan “Nick” Kraczyna (24 marzo 1940 – 1 febbraio 2026)

Swietlan “Nick” Kraczyna, figura centrale dell’arte del dopoguerra su entrambe le sponde dell’Atlantico, si è spento il 1° febbraio nella sua casa di campagna vicino a Firenze. Al suo fianco c’era la moglie, Sylvia Hetzel.

In misura davvero notevole, fu un consapevole erede del lascito intellettuale e creativo del Rinascimento italiano. Per mezzo secolo, la sua vita si è divisa tra il suggestivo centro storico di Barga — immortalato nella sua opera più celebre — e il borgo collinare fiorentino dove il pittore del Quattrocento Domenico Ghirlandaio fu maestro di Michelangelo.

A sua volta maestro, Kraczyna possedeva una rara capacità di collegare in modo tangibile il passato al presente, in conversazioni che spesso spaziavano attraverso un arco vertiginoso di letteratura, storia e scienza. Al tempo stesso, però, il suo sguardo interiore restava fisso sulla dimensione onirica e ombrosa del mondo visibile: archetipi universali, incorniciati nel mito e nella leggenda antichi, che esercitano un potere nascosto nella memoria collettiva dell’umanità.

I momenti di estasi erano spesso centrali nell’esplorazione di quel territorio, sia nella forma dell’erotismo sensuale sia in quella, a esso affine per metafora, dell’ebbrezza creativa dell’atto artistico. Le sue riflessioni sul creare alimentarono decenni di lavoro basati sul mito di Icaro, incarnazione greca del rischio immaginativo, il cui volo fatale con ali di piume tenute insieme dalla cera — sciolta dal sole — è insieme un monito e uno stimolo irresistibile. Per Kraczyna, Icaro era un precursore delle fantasie estatiche di Shakespeare nel Sogno di una notte di mezza estate e dello spettacolo allucinatorio dei carnevali. È il palcoscenico prediletto di Arlecchino, il comico ingannatore mascherato, che salta e danza negli omaggi di Kraczyna alla musica dei suoi connazionali russi, Igor Stravinskij e Pëtr Čajkovskij.

Temi e protagonisti simili attraversano gran parte della prolifica produzione di Kraczyna come incisore, alternandosi a incursioni nella fotografia e nel paesaggio pittorico. L’esempio più noto è il suo ritratto iconico di Barga, un capolavoro di colore e composizione. La città è resa come una famiglia immaginaria di pietra e mattoni, con il suo millenario Duomo come genitore protettivo che veglia su una schiera murata di case, affacciate con speranza e inquietudine sulla campagna circostante.

La stessa ambiguità senza tempo pervade la sua celebre fotografia dei fiorentini stipati su una fragile imbarcazione così stretta da offrire spazio solo per stare in piedi, colti dalle furiose acque dell’Arno in piena nel 1966. È tra le immagini documentarie più potenti del XX secolo: una rappresentazione cruda di dieci uomini e donne attoniti, improvvisamente trasformati in profughi dalle loro consuete identità di bottegai, impiegati, studenti e operai.

Sotto questo profilo, la fotografia segna un passaggio implicito verso l’autobiografia. Kraczyna nacque nella primavera cataclismica del 1940 da genitori russi di etnia in Polonia, sconvolta dalla doppia invasione della Wehrmacht nazista e dell’Armata Rossa sovietica. Lo scenario dei suoi primi ricordi è quello della distruzione totale di centinaia di città e paesi, e dei passaggi più oscuri dell’Olocausto. Nel 1945, dopo una fuga di mille chilometri attraverso territori devastati, spesso sotto il fuoco nemico, la famiglia Kraczyna fu internata in un campo profughi del dopoguerra.

Swietlan Nicholas Kraczyna aveva 11 anni quando, nel 1951, un ente caritativo religioso patrocinò il trasferimento della sua famiglia negli Stati Uniti. Nel 1962 conseguì la laurea in pittura presso la prestigiosa Rhode Island School of Design e insegnò alla Southern Illinois University fino al 1964, quando si trasferì definitivamente in Toscana con la giovane moglie, Amy Luckenbach. Luckenbach, celebre burattinaia, è scomparsa nel 2009.

Oltre ai suoi risultati artistici, Nick Kraczyna era molto stimato per i suoi laboratori di incisione — incentrati sulle sue tecniche, ampiamente influenti, di acquaforte a colori su più lastre — che attiravano studenti da tutto il mondo. Tra loro figuravano personalità di spicco come l’argentino Gabriel Feld, già preside di Architettura alla Rhode Island School of Design, e l’artista americana Maya Hardin, le cui opere sono state esposte in modo rilevante dal Metropolitan Museum of Art di New York.

Nel 1970 Kraczyna fu uno dei dieci artisti scelti per rappresentare gli Stati Uniti alla Biennale di Grafica di Palazzo Strozzi a Firenze. Insegnò in università e scuole d’arte negli Stati Uniti, in Inghilterra, in Italia, in Messico e in Colombia, e le sue incisioni fanno parte delle collezioni permanenti della Galleria degli Uffizi di Firenze e di innumerevoli altri musei. Fu coautore di I Segni Incisi, il primo manuale italiano completo sulla storia e le tecniche dell’incisione.

Oltre alla moglie, lascia i tre figli, Anna, Anatol ed Emma, e cinque nipoti.

— Frank Viviano