The green fields of Nyinawimana rise in 50 acres of carefully sculpted terraces, abuzz with honey bees under a generous sun. This might be Tuscany instead of the hills northeast of Kigali, the capital of Rwanda. And in a sense, it is. There's a powerful story here, the kind of story you seldom hear at a time when news is mostly defined as catastrophe and the notion of spontaneous human solidarity is regarded as sentimental fiction. Nyinawimana is about both of those things: gut-level solidarity and sheer unimaginable catastrophe.The beehives and high-yield farming terraces are among the landmarks of an extraordinary collaboration between rural Italians acting on their own initiative, and their Rwandan counterparts.

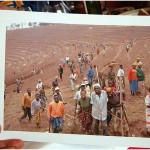

Together, in five years, they have reshaped the hills with shovels and hoes into family farm plots, created a thriving modern honey industry, built dairies and poultry facilities – an entire economy that provides work and sustenance to more than 1,000 people.

On a dollar-for-dollar basis, it may be one of the world’s most productive overseas assistance efforts, a de facto embarrassment to foreign aid programs and international charities that have spent half a trillion dollars on Africa in the past four decades to little apparent effect.

In January, The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation announced a $306 million pilot project aimed at increasing the yields and incomes of family farms in Africa. "If we are serious about ending extreme hunger and poverty around the world, we must be serious about transforming agriculture for small farmers,” Gates said.

Nyinawimana and its Italian friends are already there.

RWANDA, 1994

Fourteen years ago, in the spring of 1994, an estimated one million Rwandans died in a genocidal civil war between Tutsi and Hutu tribesmen. Part of the world’s conscience died with them.

The best that can be said about that world – from the affluent West and East Asia, to the United Nations and a phalanx of global aid institutions – is that it watched and did nothing. The worst is that some of those who watched had provided weapons to the murderers, and turned their faces away as though they bore no guilt.

“There’s a Rwandan proverb that ‘the skin of one small rabbit is enough to cover five people when there is brotherhood in the world,’” says Florent Mwiseneza, a Catholic priest who survived the 1994 genocide. “But today this proverb can sound like madness, because so many of our people have come to regard the world as ugly, blind, deaf and without feeling.”

No army of international peacekeepers was rushed to the killing fields of Rwanda, as they were in those same years to Croatia and Bosnia. No NATO air-strikes were employed against the aggressors, as they were a few years later in Kosovo.

Unlike the former citizens of Yugoslavia, the Rwandan dead were viewed as “the other,” distant and unknowable, beyond anyone’s capacity to act. To Africans, the different reactions are easily explained. The Rwandans were “the other” because they were black.

The survivors in the village of Nyinawimana remained the other, forgotten and abandoned, for seven years – until a retired mechanic and a car salesmen took notice a continent away, in a lost corner of Tuscany called the Garfagnana.

“Before the Tuscans came, there was nobody from the outside here to help us,” one of the villagers recalls. “Nobody at all.”

THE MIRROR

The Garfagnana is not the affluent, charm-soaked Tuscany of romantic novels. Framed by the high rampart of the Apennines to the east and the precipitous Apuan Alps to the west, it’s a country of marginal farmers, chestnut groves and wild mushrooms, the home of tough quarrymen whose ancestors cut marble for the Roman Forum. Many families make do on less than $10,000 per year. For generations, their children have emigrated abroad, because the Garfagnana cannot support them.

Like the farmers of Rwanda, the Garfanini understand the blunt, devastating equation of too many people trying to get by on too little arable land.

There are also few famiies in the Garfagnana that haven’t experienced the unimaginable. In World War Two, it was the setting of fierce artillery battles that levelled scores of towns and villages. In August of 1944, in revenge for the killing of a Nazi officer by Garfagnana partisans, German stormtroopers rounded up 560 people in the village of Sant’Anna di Stazzema, most of them elderly grandparents, mothers and small children, and shot them or burned them alive.

The Garfagnana was finally secured in 1945 by the 92nd U.S. Army Infantry Division, the “Buffalo Soldiers,” which sustained some of the war’s highest casualty rates, with nearly 5,000 dead or wounded on the Italian front in eight months.

The Buffalo Soldiers were African-Americans, the soldiers of a segregated army, and in their own country all but invisible. But to the people of the Garfagnana, they were heroes and liberators. (further article about the Buffalo Solders and the Congressional Medal of Honour presented to seven Buffalo Soldiers by the Clinton Admin

istration can be read here)

The Garfanini raised their children on the memory of the Sant’Anna Stazzema and the Buffalo Soldiers. In news footage from Rwanda, with its fog-shrouded mountains, its struggling farmers – and its horrifying violence – they didn’t see “the other,” a distant unknowable nation. They saw a mirror.

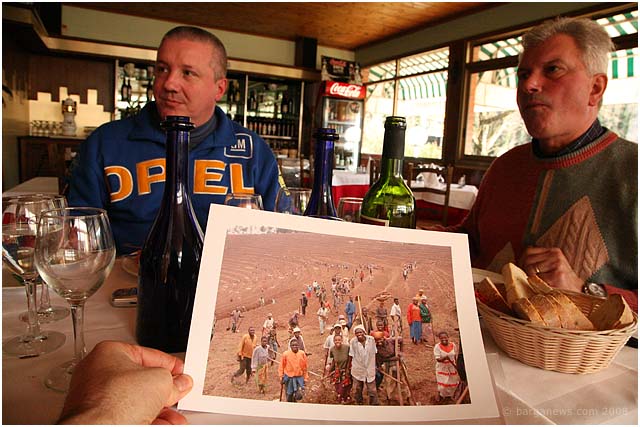

“When we watched the television, when we saw what they’d been through and were still going through, we saw our own land, our own history,” says Franco Simonini, the mechanic.

THE BIRTH OF “HOPE”

Not long after the first images of the Rwandan holocaust were belatedly aired in Italy, Franco and his neighbor, car salesman Angelo Bertolucci, began to talk seriously about Rwanda. They had no idea where their conversation would lead. “All we really knew then,” Angelo says, “is that we wanted to do something.”

Money alone, they were convinced, wasn’t the answer. It’s not the way you do things in these mountains.

“Garfagnana people are naturally generous, but a lot of them believe that for every 100 euros you donate to a charity, you’re lucky if ten get to anyone who needs help,” Angelo says. “Everywhere it’s mangia mangia,’ they tell you – “eat, eat,” a Garfanino euphemism for corruption.

More important, in Angelo’s view, is a visceral understanding that cold cash, delivered by an anonymous bureaucracy, puts money into someone’s pocket at the price of their dignity.

Instead, the two men tracked down missionaries with service in Africa, who put them into direct contact with priests and agricultural teachers in Rwanda itself. They talked to the mayors of Garfagnana towns, asking their support. With the help of local bankers, they formed a non-profit corporation and called it Kwizera, Rwandan for “Hope,” with Franco as president and Angelo as secretary.

In 2001, Angelo and Franco flew via Rome and Cairo to Rwanda, “to look around, to ask what we could do.” They carried a suitcase of suggestions and blueprints from Garfagnana farmers, engineers, stone masons, veterinarians and tradesmen, and the equivalent of $25,000 to get things rolling.

As they have on a total of 14 trips between them – as have all the Garfanini who have traveled to Rwanda – Angelo and Franco paid for their own tickets.

The Lake Angels, a group of local men from the hilltown of Barga, are typical of those who heard about Kwizera. The group’s name came from their annual hikes to Lago Santo, a lake deep in the Appennines. “We grew up together, and at first these walks were just a way for us to remain close,” says Alessandro Gonnelli, a plumber. “We drank a lot of wine, we told stories, we talked all night.” On several of their long nights at Lago Santo, they too talked about Rwanda.

The Angels set up a stand at Barga’s annual summer music festival, serving wine from their own small vineyards, Later they expanded to fresh Garfagnana sausages and bacon, prepared by an Angel who runs a butcher shop, and Christmas baskets bearing their olive oil, wine, chestnuts and dried porcini mushrooms. By 2007, the group's yearly contribution to Kwizera surpassed $10,000. (all the Lake Angels activities can be seen here)

FROM ANCIENT ROME TO RWANDA

The Garfagnana’s African mission has since grown to nearly $500,000 worth of projects. That doesn’t sound like much, compared to $500 billion in official foreign aid to sub-Saharan Africa since 1970. But when you look at results, it is the legacy of that half trillion dollars in official aid that seems trifling.

This is the failure Bill and Melinda Gates implicitly hope to reverse: decades of vast expenditures that have changed almost nothing for the small farmers who are Africa’s backbone.

In addition to buying 50 acres of land above Nyinawimana and joining forces with 400 local farmers to terrace it by hand into arable plots, the Tuscans of Kwizera have constructed stables, cisterns, schoolrooms and housing for agricultural workers. Along with modern bee-raising and poultry-breeding, they have introduced new breeds of goats and cows. “Rwandan cows are very sturdy, but of a type raised only for meat, and very few families can afford one,” explains Paul Gahutu, a local teacher.

When Franco and Angelo learned that the average milk output one of those cows was less than two quarts per day, they organized and financed a farmer’s shopping trip to Uganda. Today, Ugandan cows that produce 15-20 quarts per day graze the terraces of Nyinawimana.

In June, the Lake Angel plumber Alessandro Gonnelli will travel to the village with plans for a permanent irrigation system, in hills that are deluged with rainfall ten weeks each spring and bone dry the rest of the year.

His plan “uses the technology of the Roman Empire,” Gonnelli tells a reporter, pointing at an ancient aqueduct that has served the Garfagnana for centuries. The idea is to create a network of catch-basins and pipes that will channel rainwater down the terraces into holding tanks for use in the dry months, making an extra growing season possible. “It’s a very basic system that will do its job and last a long, long time,” he says.

That’s a succinct description of the hope Kwizera has carried from rural Italy to rural Rwanda, through a mirror that makes all the difference in the world.

– Frank Viviano – barganews staff reporter – World View CBS5

The Kwizera site is here | the Lake Angles are here |