LUNGO LA SPONDA DEL MIO DOLCE FIUME IMMAGINI E STORIE LUNGO LA CORSONNA

ON THE BANKS OF MY SWEET RIVER IMAGES AND STORIES ALONG THE CORSONNA

FONDAZIONE RICCI

Review by Frank Viviano

It would be impossible to exaggerate the role of a small but insistent riverlet, the Torrente Corsonna, in the history of Barga.

Since time immemorial, the river has nurtured the summer dreams of children. The annual building of stick-and-pebble dams on its narrows to form natural swimming pools was a June ritual for generations beyond count. The Corsonna furnished their families’ daily bread with flour ground by its current-driven grain mills. For the town’s devout Catholics, one of those mills was the setting of a miracle, the discovery in 1512 of the Madonna del Mulino, an enigmatic Byzantine painting which believers credited with protecting them from the Plague.

In a larger sense, Barga owes its very foundation to the Corsonna: a reliable source of fresh water that spawned a walled settlement on the hill where the Duomo now stands, offering safety from armed marauders who ravaged the Serchio Valley for a dozen centuries between the fall of Rome and the Renaissance.

This summer, the Torrente is the subject of two extraordinary exhibitions. A series of luminous oil paintings of the river and its long-deserted mills by the artist Keane, founder of Barganews, is on view at the Palazzo Pancrazi until the end of August. It was followed on July 29 by a second, much larger mostra at the Fondazione Ricci, which continues until October 15. The Ricci collection plumbs the river’s deep significance, both literal and emotional, in the saga of Barga — and spotlights a new name on the remarkable list of this small town’s outsized roster of brilliant artists: Caterina Salvi Westbrooke.

**********

The visitor is welcomed at the door of Villa Caproni, Ricci’s elegant Liberty-style home, by a forest gnome, perched on a mushroom and peering out from an opening in the trunk of a tree. The work of sylvan sculptor Luigi Paolini, it is a reminder of the region’s pre-Roman inhabitants, the Liguri, worshippers of woodland gods.

The ground-floor lobby beyond presents an authoritative overview of Corsonna geology, vegetation, marine and forest life, as well as its representation in literature. In effect, it amounts to a de facto encyclopedia of the Corsonna, curated by Foundation president Cristiana Ricci and historian Sara Moscardini in two years of painstaking research. Of particular interest are a series of rare historical maps of the river’s course and Barga itself, turned up by Ricci in sources as far-flung as Prague, and Moscardini’s astute compilation of references to the river by the celebrated poet Giovanni Pascoli and other writers. In an adjacent auditorium, video interviews of Barghigiani who have resided on the Corsonna’s banks describe the hardships and pleasures of life there.

A gathering of Corsonna driftwood stands at the lobby’s far end, transformed by Marco Poma into gilded renditions of what he calls “spiritelli,” kindred cousins of Paolini’s gnome. Nearby, carvings of Barga’s coat of arms and the Madonna del Mulino, sculpted from local stone by Leo Gonella, recall the heraldic monoliths of imperial Rome.

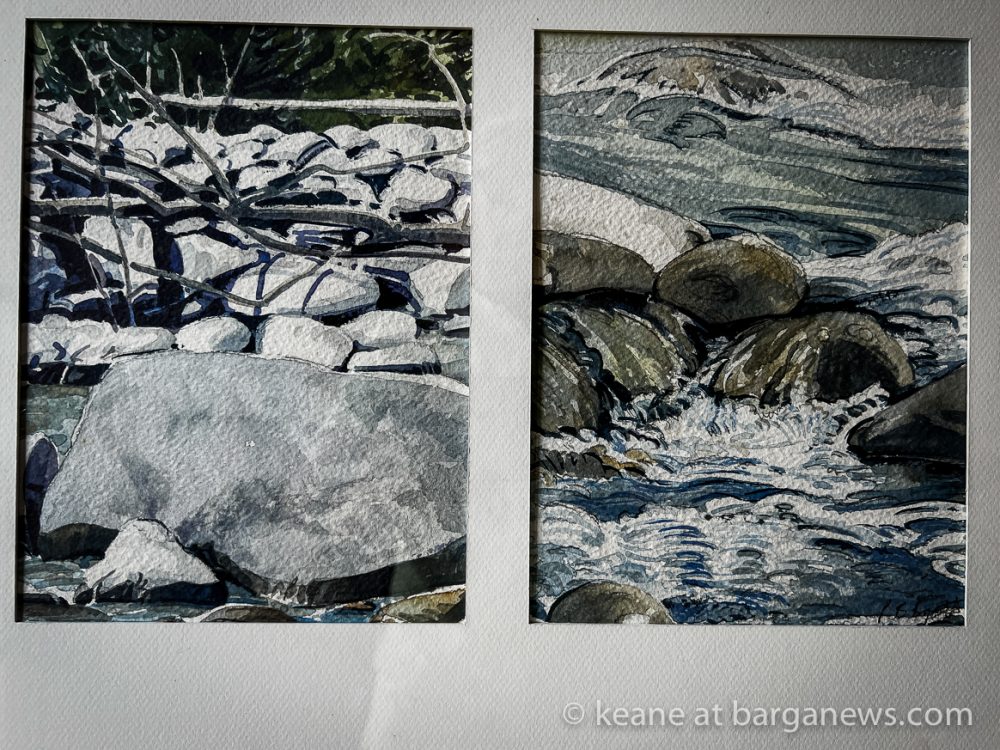

They gate-keep a staircase framed by multiple portraits of the Corsonna and its surroundings by notable Barga artists, led chronologically by Umberto Vittorini, Adolfo Balduini and Bruno Cordati, major figures in 20th century Italian art, and the lesser-known but supremely talented Persio da Prato. An enormous oil by contemporary painter and photographer Giorgia Madiai, executed with characteristic intensity, hangs over the stairs. Their upper stretch features depictions of the river by Keane, Peter Byatt, Swietlan Nicholas Kraczyna and Helen Bellany.

A suggestive feeling of anticipation grows as one climbs, a sense that this parade of creative genius is building toward an epiphany. Its author is Caterina Salvi Westbrooke, and her contributions fill the entire second floor of Villa Caproni.

**********

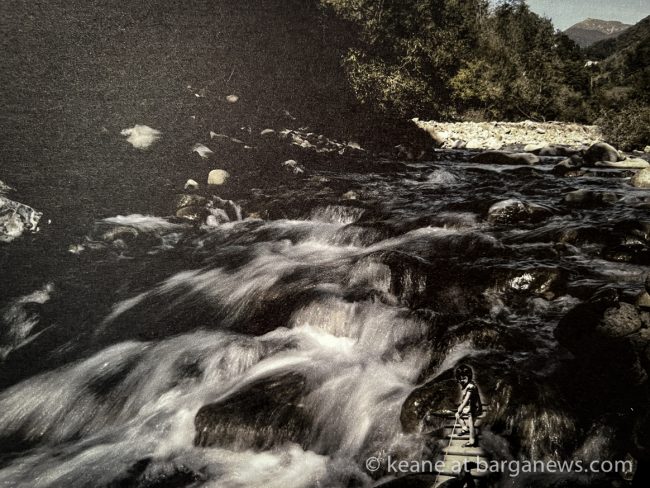

Put simply, Salvi has assembled a show-stopper, dazzling in its technical mastery and deeply moving in its sheer emotional power. Over a circuit of six linked rooms, she explores the Corsonna through the lens of her chosen profession — photography, the youngest of our fine arts — in a visual symphony on its spell-binding possibilities.

The eye of the artist is the central component of photographic art, the formidable ability to recognize and frame compositions that are full of meaning as well as beauty and grace. Salvi manifestly has that eye, and in her company we are led on a spectacular journey. Its landmarks are eloquent variations on the partnership of light and shadow that infuses all photographs, accompanied by experiments with inserted “found images,” borrowed from nameless albums, and with the materials on which photographic images can be printed.

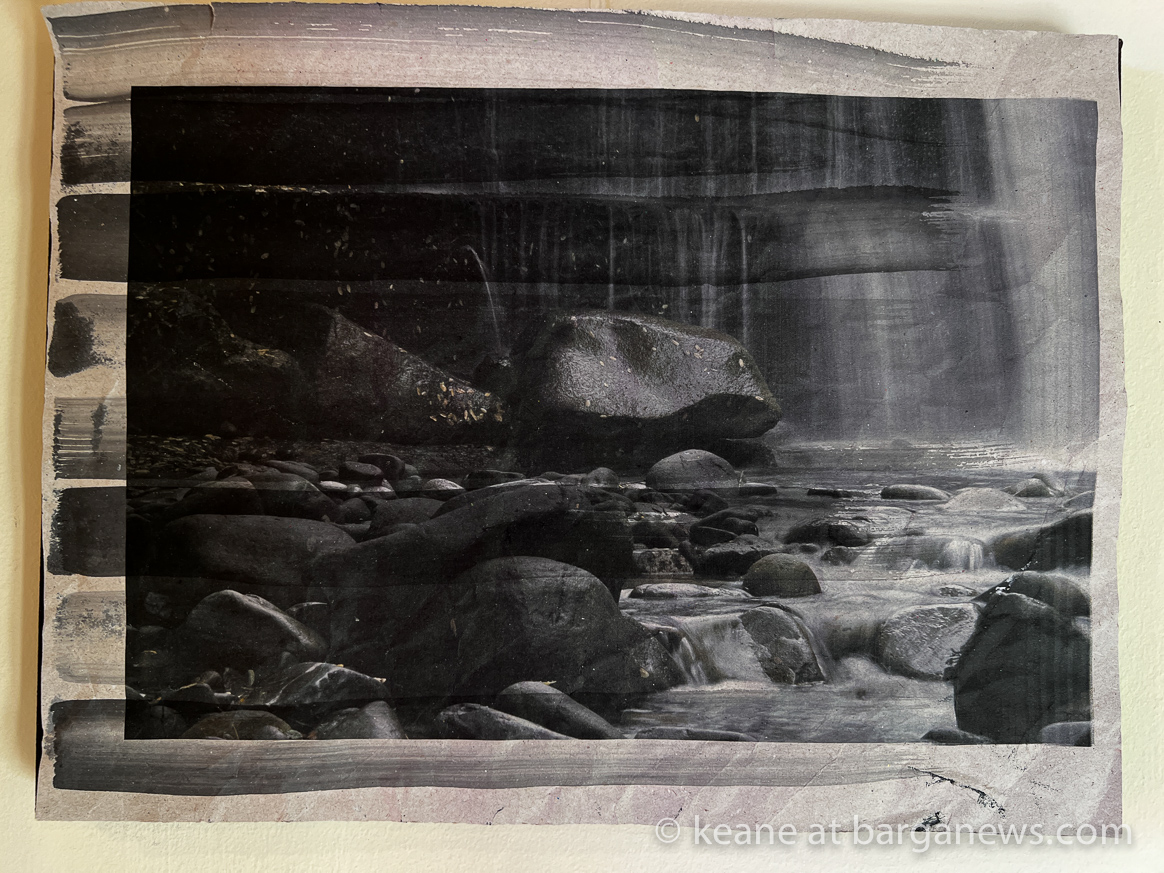

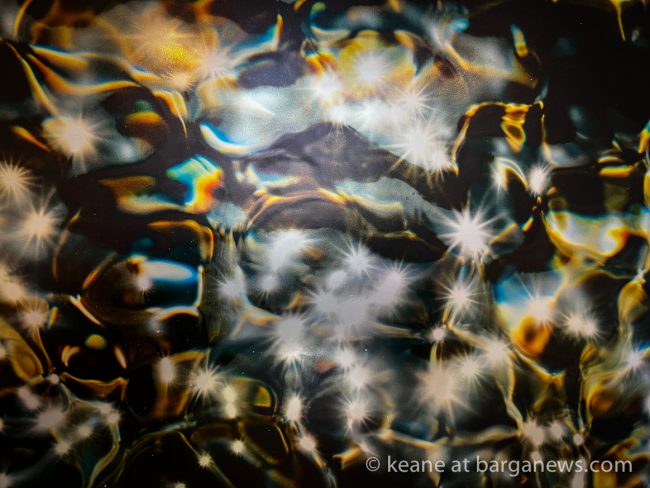

No commercial lab was involved in these experiments. Salvi herself carried out the printing: on standard photographic paper, both matte and glossy; on metallic sheets that capture the brushed-steel quality of rock faces polished by rapids under a bright sun; and on Japanese “washi,” the delicate calligraphy medium favored by the great 19th century landscapists Hiroshige and Hokusai.

There is also a nod to evolving technologies and their impact on photography: aerial views of the Corsonna taken by a drone camera, and still-life clusters of flowers and branches that have been arranged and copied on electronic scanners and involve no camera at all.

But a more profound journey also unfolds in this circuit, and it marks an about-face in our understanding of photography’s possibilities, which typically focus on its capacity for preserving a single brief moment in place and time. By contrast, the subtext of “Along the Corsonna” is measured out in months rather than split-seconds. “For three years,” Salvi says, “I walked the Corsonna every single day, through every season, in the rain and under the sun.”

Indeed, the succession of seasons is among the overt subjects of the mostra, but so too are more subtle and personal themes, chief among them the peace that human beings have sought in solitary communion with nature since the classical world of Homer’s Greece and Virgil’s Rome, and surely long before them.

In November 2018, Caterina’s father Luigi Salvi, for decades a reassuring presence in Barga’s public life and a paragon of calmly effective leadership, passed away after a devastating illness. Just 14 months later, Covid-19 struck Italy, the pandemic’s first and most catastrophic assault on the western world. For the following two years Barga reeled with fear, tension, stringently imposed isolation and cascading deaths.

The daily hours spent on the Corsonna were Caterina Salvi’s retreat, and its seasonal fluctuations her consolation. Her healing. Its progress is solemnly charted on these walls, by unspoken inference rather than overt allusion, most poignantly in the image of a hand motionless under the river’s surface.

It is at once Caterina’s own hand and that of her father, the hand she held as he died.

Article by staff reporter of barganews, Frank Viviano, a journalist nominated 8 times for the Pulitzer Prize and bestselling author. All of Frank Viviano’s articles on barganews can be viewed here.

|

|

|

|

LUNGO LA SPONDA DEL MIO DOLCE FIUME IMMAGINI E STORIE LUNGO LA CORSONNA

Recensione di Frank Viviano

Sarebbe impossibile esagerare il ruolo di un piccolo, ma insistente torrente, il Torrente Corsonna, nella storia di Barga.

Fin dai tempi immemorabili, il fiume ha nutrito i sogni estivi dei bambini. La costruzione annuale di dighe di bastoncini e ciottoli sulle sue strettoie per formare piscine naturali era un rituale di giugno per generazioni senza contare. Il Corsonna forniva il pane quotidiano alle loro famiglie con la farina macinata dai mulini a grano azionati dalla sua corrente. Per i devoti cattolici della città, uno di quei mulini fu il luogo di un miracolo, la scoperta nel 1512 della Madonna del Mulino, un enigmatico dipinto bizantino che i credenti attribuivano il potere di proteggerli dalla Peste.

In senso più ampio, Barga deve la sua fondazione stessa al Corsonna: una fonte affidabile di acqua dolce che ha generato un insediamento fortificato sulla collina dove ora sorge il Duomo, offrendo protezione dai predoni armati che hanno saccheggiato la Valle del Serchio per una dozzina di secoli tra la caduta di Roma e il Rinascimento.

Quest’estate, il Torrente è oggetto di due straordinarie mostre. Una serie di luminosi dipinti ad olio del fiume e dei suoi mulini da lungo tempo abbandonati dell’artista Keane, fondatore di Barganews, è in mostra al Palazzo Pancrazi fino alla fine di agosto. È stata seguita il 29 luglio da una seconda, molto più grande, mostra presso la Fondazione Ricci, che prosegue fino al 15 ottobre. La collezione Ricci indaga il profondo significato del fiume, sia letterale che emotivo, nella saga di Barga, e mette in luce un nuovo nome nell’impressionante lista degli artisti brillanti di questa piccola città: Caterina Salvi Westbrooke.

Il visitatore è accolto all’ingresso di Villa Caproni, l’elegante casa in stile Liberty di Ricci, da un folletto del bosco, appollaiato su un fungo e che spia dall’apertura nel tronco di un albero. Opera dello scultore silvano Luigi Paolini, è un richiamo agli abitanti pre-romani della regione, i Liguri, veneratori degli dei del bosco.

Il foyer al piano terra presenta un’autorevole panoramica della geologia, vegetazione, vita marina e forestale del Corsonna, nonché la sua rappresentazione nella letteratura. In effetti, si tratta di un’enciclopedia de facto del Corsonna, curata dal presidente della Fondazione, Cristiana Ricci, e dalla storica Sara Moscardini, in due anni di meticolose ricerche. Di particolare interesse sono una serie di rare mappe storiche del corso del fiume e di Barga stessa, scoperte da Ricci in fonti sparse fino a Praga, e l’attenta compilazione di Moscardini dei riferimenti al fiume da parte del celebre poeta Giovanni Pascoli e altri scrittori. In un auditorium adiacente, interviste video a barghigiani che hanno vissuto sulle sponde del Corsonna descrivono le difficoltà e le gioie della vita lì.

Un gruppo di legni galleggianti del Corsonna sta all’estremità lontana del foyer, trasformati da Marco Poma in dorati esemplari di ciò che chiama “spiritelli”, parenti affini del folletto di Paolini. Vicino, le sculture dello stemma di Barga e della Madonna del Mulino, scolpite in pietra locale da Leo Gonella, richiamano i monoliti araldici dell’impero romano.

Essi fanno da guardia a una scala incorniciata da numerosi ritratti del Corsonna e dei suoi dintorni di noti artisti di Barga, guidati cronologicamente da Umberto Vittorini, Adolfo Balduini e Bruno Cordati, figure importanti nell’arte italiana del XX secolo, e dal meno conosciuto ma supremamente talentuoso Persio da Prato. Un enorme olio del pittore e fotografo contemporaneo Giorgia Madiai, eseguito con intensità caratteristica, sovrasta le scale. La loro parte superiore presenta raffigurazioni del fiume di Keane, Peter Byatt, Swietlan Nicholas Kraczyna e Helen Bellany.

Una suggestiva sensazione di attesa cresce salendo, un senso che questa parata di genio creativo si sta costruendo verso un’epifania. L’autrice è Caterina Salvi Westbrooke, e i suoi contributi riempiono l’intero secondo piano di Villa Caproni.

Semplicemente, Salvi ha messo insieme una mostra straordinaria, affascinante per la sua padronanza tecnica e profondamente commovente per la sua pura forza emotiva. Attraverso un circuito di sei stanze collegate, esplora il Corsonna attraverso la lente della sua professione scelta: la fotografia, la più giovane delle nostre belle arti, in una sinfonia visiva sulle sue affascinanti possibilità.

L’occhio dell’artista è il componente centrale dell’arte fotografica, la formidabile capacità di riconoscere e inquadrare composizioni ricche di significato, bellezza e grazia. Salvi manifestamente possiede questo occhio, e con lei siamo guidati in un viaggio spettacolare. I suoi punti di riferimento sono eloquenti variazioni sulla partnership di luce e ombra che permea tutte le fotografie, accompagnate da esperimenti con “immagini trovate” inserite, prese da album anonimi, e con i materiali su cui le immagini fotografiche possono essere stampate.

Nessun laboratorio commerciale è stato coinvolto in questi esperimenti. Salvi stessa ha eseguito la stampa: su carta fotografica standard, sia opaca che lucida; su fogli metallici che catturano la qualità dell’acciaio spazzolato delle pareti rocciose lucidate dai rapidi sotto un sole brillante; e su “washi” giapponese, la delicata tecnica calligrafica favorita dai grandi paesaggisti del XIX secolo Hiroshige e Hokusai.

Vi è anche un cenno alle tecnologie in evoluzione e al loro impatto sulla fotografia: vedute aeree del Corsonna scattate da una telecamera drone e composizioni di fiori e rami che sono stati disposti e copiati su scanner elettronici e non implicano alcuna fotocamera.

Ma un viaggio più profondo si svolge anche in questo circuito, e segna un cambio di rotta nella nostra comprensione delle possibilità della fotografia, che di solito si concentrano sulla sua capacità di conservare un singolo breve momento nello spazio e nel tempo. Al contrario, il sottotesto di “Lungo il Corsonna” è misurato in mesi piuttosto che in frazioni di secondo. “Per tre anni”, dice Salvi, “ho camminato lungo il Corsonna ogni giorno, in tutte le stagioni, sotto la pioggia e sotto il sole”.

In effetti, il susseguirsi delle stagioni è tra i soggetti evidenti della mostra, ma lo sono anche temi più sottili e personali, soprattutto la pace che gli esseri umani hanno cercato nel solitario contatto con la natura sin dai tempi classici della Grecia di Omero e della Roma di Virgilio, e certamente molto prima di loro.

Nel novembre del 2018, il padre di Caterina, Luigi Salvi, per decenni presenza rassicurante nella vita pubblica di Barga e modello di leadership serena ed efficace, è scomparso dopo una devastante malattia. Appena 14 mesi dopo, l’Italia è stata colpita dal Covid-19, il primo e più catastrofico assalto della pandemia al mondo occidentale. Per i due anni successivi, Barga ha vissuto tra paura, tensione, isolamento rigorosamente imposto e morti in cascata.

Le ore quotidiane trascorse sul Corsonna sono state il rifugio di Caterina Salvi e le sue variazioni stagionali la sua consolazione. La sua guarigione. Il suo progresso è solennemente tracciato su queste pareti, per implicazione non dichiarata piuttosto che esplicito riferimento, in modo più struggente nell’immagine di una mano immobile sotto la superficie del fiume.

È al tempo stesso la mano di Caterina e quella di suo padre, la mano che teneva quando è morto.

Articolo dello staff del reporter di barganews, Frank Viviano, un giornalista nominato 8 volte per il Premio Pulitzer e autore di bestseller. Tutti gli articoli di Frank Viviano su barganews possono essere visualizzati qui.